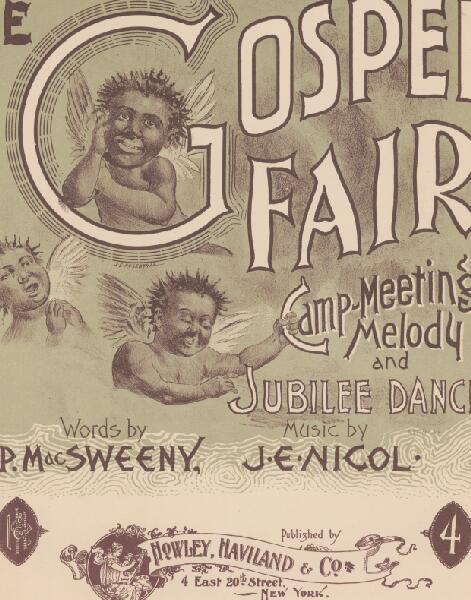

De Gospel Fair

1895-01-01

J. P. MacSweeny;J. E. Nicol

Added June 12, 2025, 2:36 p.m.

Dyer's Pslamist

1853

Sidney Dyer

Added Jan. 14, 2025, 5:43 p.m.

Harp of the South

1853

I. B. Woodbury

Added March 6, 2025, 3:25 p.m.

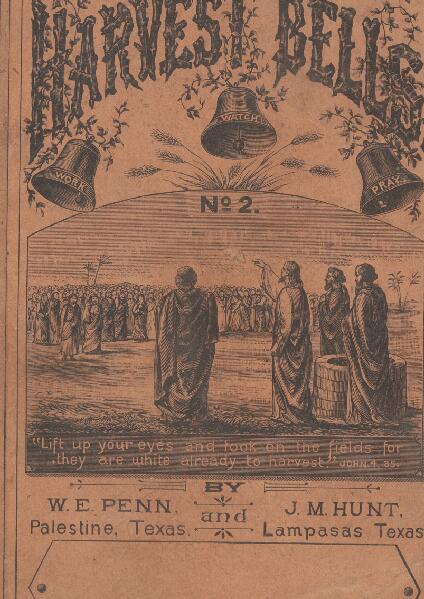

Harvest Bells No. 2

1884

W. E. Penn;J. M. Hunt

Added March 20, 2025, 7:49 p.m.

Hymns and Tunes

1868-01-01 00:00:00

George C. Robinson

Added Dec. 10, 2025, 8:38 a.m.

Jasper and Gold

1877

T. C. O'Kane

Added March 6, 2025, 3:25 p.m.

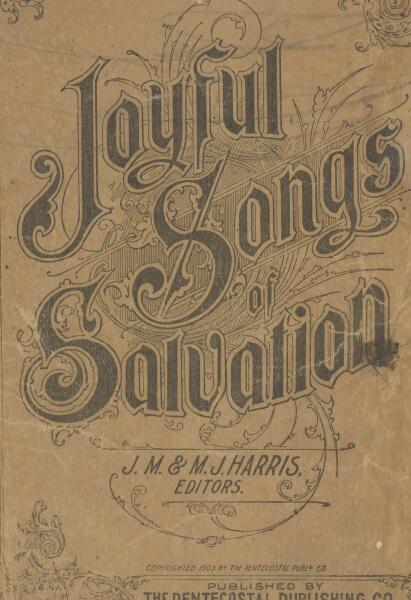

Joyful Songs of Salvation

1903-01-01

J. M. Harris;M. J. Harris

Added May 7, 2025, 8:21 a.m.

Ministry in Song

1909-01-01 00:00:00

W. C. Everett;E. O. Excell

Added Aug. 5, 2025, 10:55 a.m.